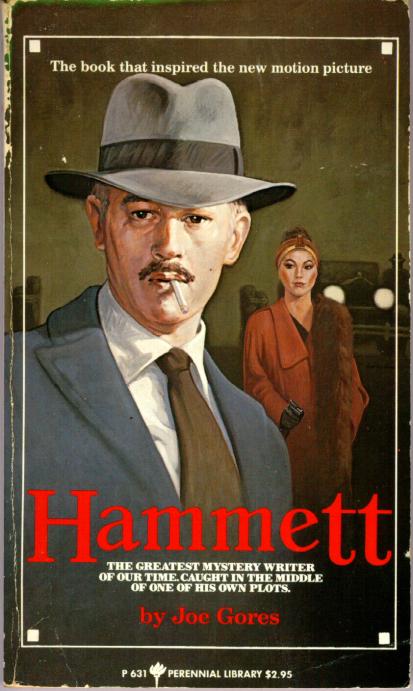

The greatest mystery writer of our times caught in the middle of one of his own plots.

Author: Joe Gores

First published in 1975. Copy reviewed: 1982, Harper & Row

Softback novel - 251 pages

ISBN: 0-06-080631-1

Price: Out of Print

|

Hammett The greatest mystery writer of our times caught in the middle of one of his own plots. Author: Joe Gores First published in 1975. Copy reviewed: 1982, Harper & Row Softback novel - 251 pages ISBN: 0-06-080631-1 Price: Out of Print |